A review of Venetian Glass by Carlo Scarpa: The Venini Company, 1932-1947 (Nov. 5, 2013 – March 2, 2014), written by JoAnn Locktov.

“Scarpa had this thing for detail that would kill you with pleasure.”

Ida Barbarigo Cadorin, painter (b 1925, Venice)

The Unbearable Lightness of Scarpa

To understand the glass that architect Carlo Scarpa created for Venini one must travel back in time—before 1906, the year of his birth in Venice, before Napoleon and the Austrians had their way with the floating city, and even before Casanova escaped from prison and rowed a gondola to freedom.

The fires in the glass furnaces on Murano have been stoked for eight centuries. It is natural that the Venetian craftsmen with their artistic lineage that dates from the 13th century would have a deep affinity for glass. Apprehensive about potential fires and the unlawful sharing of professional secrets, all glassmaking moved to Murano by 1271. The discoveries were astounding; gold leaf graffito, crystal, lattimo milk glass, filigree, incalmo, mirrors. millefiore, reading glasses – all put into production on Murano with attendant patents by the middle of the 16th century.

Scarpa Had a Fascination With Glass

Armed with his degree in architectural drawing and a fascination with this material that evokes water and light—the quintessential elements of Venice—the 20 year-old Scarpa embarked on a journey that would continue this ancient Venetian tradition.

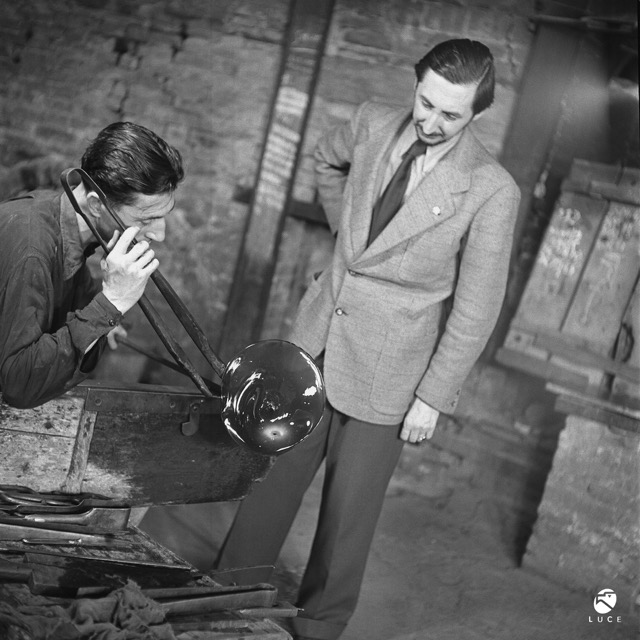

It was the glass manufacturer M. V. M. Cappellin who first invited the young architect to Murano to restore the gothic Palazzo Da Mula in 1926. Did Capellin suspect that glass would dominate the architect’s life for the next 20 years? Cappellin did not prosper and declared bankruptcy in 1931. The next year Scarpa became the artistic director of Venini. He submerged himself in the spirit of glass making. Not content designing during daylight hours he would spend the night at the foundry to study how the glass was born; its characteristics in infancy. He worked in concert with the maestri, experimenting, investigating, and demolishing boundaries to realize new techniques, patterns, color combinations, and textures.

In 2013 the Metropolitan Museum of Art had a 300-piece inclusive display of the work that was created during the 15-year period of Scarpa’s collaborations at Venini. It originated in Venice at Le Stanze del Vetro, the gallery on San Giorgio Maggiore devoted to glass exhibitions. In addition to offering more space for visitors to circumnavigate the vitrines (designed by the architect Annabelle Selldorf who created them for the original exhibit), the Met’s curators also pulled from their museum’s formidable collection and included Asian porcelain, 19th century Italian glass and ancient Roman murrine to help visitors better understand Scarpa’s design inspirations and historic precedents.

Detailed wall texts throughout the exhibition described Scarpa’s techniques and at the end of the exhibit there was a brief presentation that places Scarpa’s glasswork in the context of his architectural work, which followed his fertile period at Venini. At the preview Nicholas Cullinen, the curator of the Met’s exhibit, commented on Scarpa’s “restless innovation;” mastering a technique and moving on every two years. As the wall text attests, the majority of glasswork was exhibited at the Venice Biennale and the Milan Triennial, which I suspect strongly motivated Scarpa to conquer and innovate every two years. He was, in fact, a consummate marketer, insisting in his 1945 contract that his name be included in all exhibits and denoted as “artistic collaborator.”

In the late sixties there was student protest at many universities and Venice was not immune. Scarpa marched into the Instituto Universitario di Architettura, Venezia (IUAV) where he was the director and tore down banners and removed protest signs. It wasn’t the politics he was upset about; he felt the students should be ashamed of their bad lettering. I had the same response to the blue banner that greeted visitors to the exhibit.

Venetian Glass by Carlo Scarpa Was Ordered Chronologically

The glass at the Met exhibition was ordered chronologically and by technique, peppered with photographs of Scarpa and drawings from the foundry. Scarpa was an inveterate draftsman; his architectural drawings in colored pencil with layers of transparent paper are an intricate testament to his process. His glass drawings are naively simple; they feel almost hasty, as if he could barely wait to get from pencil to glass. There is one particular drawing that captures Scarpa’s legendary enthusiasm. He was designing a corroso gold bowl for Countess Volpi (her husband amongst other things founded the Venice Film Festival in 1932) and alongside the drawing of the bowl Scarpa demands that you listen to him, invoking the imperative with the addition of multiple exclamation points. It is a humble and revealing sketch of passionate innovator.

His vessels and plates are magnificent journey though centuries of glass making in the hands of a modern alchemist. I had to remind myself often that the work I was viewing was not created yesterday, but in the 30’s and 40’s. The 300 works exemplify a mind that that was consumed with light, color, opacity, fragility, irony, history, and poetry. Scarpa did not only look to the legacy of the ancient Romans; he ventured to Asia and Byzantium, and circled back home to his gold-infused city of reflection. Ruskin wrote that the laws of glass could not be forced because craftsmen must follow the rules that govern the synergy between sand and fire. Experiencing the body of work that Scarpa created belies Ruskin’s theory. His profound manipulations of glass clearly show who was boss.

There were also radical interventions. There was glass that erupts in brutal bumps, atavistic glass that looks archaic, iridescent glass that changes color with the light, and glass so saturated it mimics ceramic. Scarpa looked to the past and to the east, but he also looked to the very bottom of the refuse bin. With his devotion to material and insatiable curiosity Scarpa found inspiration in the sediment of scraps.

Guido Pietropoli, an Italian architect who studied and worked with Scarpa, contributed a poignant essay to Mario Barovier’s comprehensive exhibition catalogue. He wrote about Scarpa’s “beautiful and remarkable hands,” and his ability to “…evaluate the nature of materials just by brushing against them briefly.” During his tenure at Venini Scarpa formed the basis for the rest of his architectural career. His fascination with glass extended to all the materials he would dominate and incorporate into his building–ebony, rosewood, brass, marble, terrazzo, mosaic, and plaster. Scarpa treated each medium with respect as he bent them to his formidable artistry.

ca. 1938–1940. Private collection; Private collection; Chiara and Francesco Carraro Collection, Venice; European Collection.

In Cullinan’s erudite catalogue essay he acknowledges that the exhibit, “aims to augment his growing, if not fully realized, international reputation.” The exhibit was not only a first in 20th century Murano glass for the Met, for many it was their first introduction to the work of Carlo Scarpa. It feels right for this enigmatic Venetian architect that our acquaintance began with his exquisite glass because it remains the filament of his life’s work. Scarpa felt that architecture could be poetry but he also admitted that society does not always ask for poetry. Perhaps it is time for us to be reminded.

To read other articles JoAnn Locktov has written about Scarpa, click through to The Measure of a Man and A Sonnet in Silver.